Brexit voters, enraged by the amount of red tape and EU laws that we are subjected to, will find little relief when it comes to emissions legislation concerning diesel engines. As will be the case in many sectors, engineers will need to design to European or global standards if they intend selling their products in to those markets. Diesel engines, particularly for larger off-road vehicles, are typical of this as no OEM is going to want to design a vehicle just for a home market.

Not that the UK would necessarily want to ignore such legislation. The World Health Organisation has classified Particulate Matter (PM) as carcinogenic, and there is increasing evidence of the harmful effects of Nitrogen Oxides (NOx).

However, meeting the Stage 4 EU legislation has been demanding and the move to Stage 5, although three or four years away (depending on engine size), will demand air coming out of an exhaust being cleaner, at least in terms of PM and NOx, than it was when entering the engine. Stage 6 lurks a decade or more away, and presumably by that time the diesel engine will be regarded as an air purification device. It is a tough ask and unsurprisingly many OEMs are already making preparations.

Designing a vehicle that will be compliant is no easy task. It will be an evolutionary process but one that will be complicated by the route that was taken when meeting the demands of Stage 4. Going back a step further, Stage 3 emissions could be dealt with within the engine’s cylinder, the last legislative tier where this was possible. Stage 4 signalled a change in technology requirements – after treatment has become a necessity.

Engines can be developed to reduce harmful emissions but there is a trade-off. Reducing NOx typically increases PM and vice versa, and this affects the nature of the after treatment. A low NOx engine with high PM will typically be dealt with by a diesel oxidation catalyst (DOC) along with a diesel particulate filter (DPF). The alternative route is to go for a low PM engine with high NOx levels that then would require treatment using a DOC and selective catalytic reduction (SCR).

It should be pointed out that carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons are also included in the legislation, but they are removed by using the processes for NOx and PM. Another aspect of the Stage 5 is that it will distinguish between engine size. So engines down to 19kW (25 horsepower), that’s lawnmower size, will have certain emission restrictions and these become more stringent after 56kW (75hp).

Implementing a strategy to tackle emissions compliance is not a straightforward task for most vehicle manufacturers. Simply adding more filters and treatment plants under the bonnet is not an option.

Bob Laing, product development manager at Eminox, explained: “Generally OEMs will do a facelift based on the emissions change as well. The reason being is it has such an impact is the considerable space it claims within the vehicle. Generally, there’s not really that much space available. So when they’ve actually got to go round again, and to do the redesign and put all of this equipment in, they find that they’ve got to move major components. So therefore it’s almost easier to start from scratch.”

Laing says Eminox are already a considerable way along the path of developing solutions for its OEM customers. He said: “As we move to Stage 5, the emissions standards have become so tight that virtually no-one can get through the standard without bringing all of these elements together. So all of the greater than 56kW will go with the DOC, some type of particulate filter, an SCR, and then what we call a clean-up catalyst.”

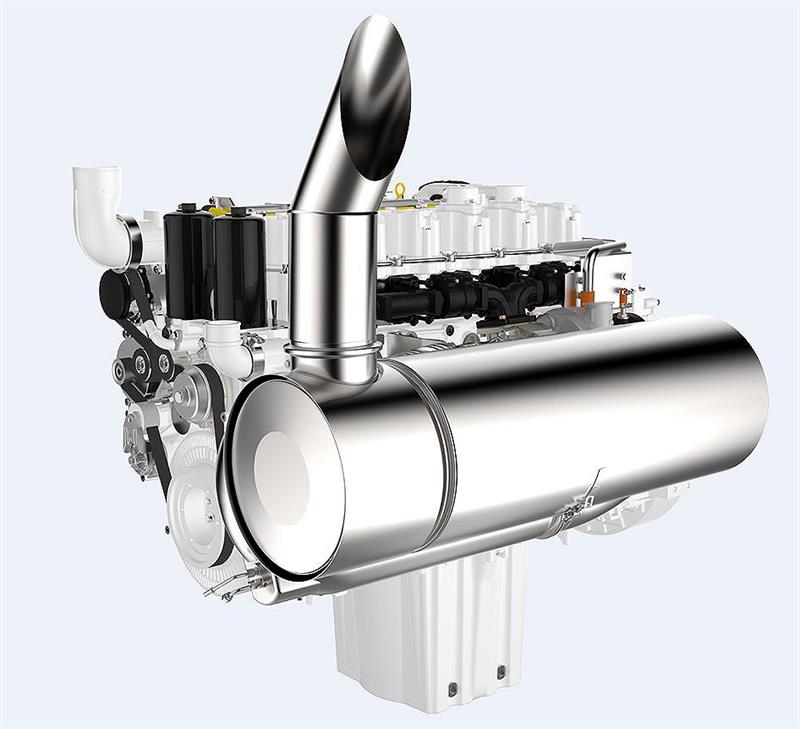

An engine fitted with Eminox SCR

Companies who went down the DOC/SCR route add a second fluid to the catalytic converter. This fluid, AdBlue, is a urea in water solution, that converts NOx into environmentally acceptable bi-products, principally nitrogen and water.

This reaction is temperature dependent as are other catalytic options and the passive regeneration within the filters. Temperature management therefore becomes critical in assessing the capability of the converters, but the most important consideration is the amount of space the OEM allows.

“We understand the packaging space that they’ve got available, and the engine guys set emissions targets,” said Laing. “The targets then drive an initial sizing of the bricks [the cordierite filters] which is the biggest constraint. Some of these can be 13-inch diameter, by 18 or 20-inches, and that would be one can. And inside that we have an inlet, a DOC, a DPF and an outlet to potentially an SCR mixer section. You may have two cans like that.”

The design process flow starts with Eminox taking collaborating with the OEM to create CAD files. Initial CFD will assess the ability of the design to achieve the necessary gas flows and the temperatures.

Laing continued: “Once we’ve got a package locked down and we’re quite happy that it fits, it meets the emissions tier, we’ve got the substrates in there, we’ll then move to a much more in-depth study. We’ll use CFD to then make sure that the gas, as it goes round the corner, actually hits the full front face of the catalyst. What you can’t do is have a very tight bend and then have the gas only hit a portion of the catalyst, because then you’re just wasting money. The efficiency of the system must be very high. We’re actually looking at above 96% to 98% of the gas hitting the full front face of the catalyst.”

Satisfied that the system works in principle the next stage is to move on to the bracket stacks, the mounted system, to make sure the system is sound. An NVH (noise, vibration and harshness) study ensures that there is no disruptive noise from the system.

The overall goal is to make systems that are lighter, cheaper and smaller. Improvements in catalysts should help along this road but there are immediate subtleties that can make a big difference.

“Alongside identifying the right type of catalyst for the right job, there are things like mixing technologies,” commented Laing. “If you can do a good job of mixing, you can do that in smaller space leading to systems that are more compact and lightweight. It is where we add a lot of value in what we call close proximity mixing, allowing the systems to still achieve high performance in terms of emissions reduction, but in a more compact space.”

Good engineering can satisfy the demands of current legislation, but what happens when we move to Stage 6?

“We're actually at a point where the particulate matter is so low and the NOx is being controlled to such a level, that the legislators have got to go after something else,” said Laing.

But what are they going to go after and to what level? In or out of Europe, we will need to find the answers.