Air pollution categorically effects health on a global scale. Reports from the World Health Organisation claim 3 million people die prematurely each year because of air pollution. It shortens lives and causes a number of related health problems. Rightly or wrongly, the VW emissions scandal has meant that more blame is being ushered towards the internal combustion engine, which is set to be increasingly demonised as a population killer in the same way as cigarettes.

Repeated calls to control emissions are certainly being heard but effective action to address the problem has been slow to materialise. The pressure is now squarely on the shoulders of engineers to find viable replacements for the 20th Century workhorse.

“It needs to be recognised that all sectors have been able to heavily reduce CO2 emissions except transportation,” says Dr Wolfgang Warnecke, the chief scientist for mobility at Shell.

He explains that despite billions going into efforts to clean up exhaust emissions, transport has been unable to improve efficiency compared to other sectors with industry finding improvements of 32%, housing 34% and energy generation 22% between 1990 and 2015. Transport, by comparison, has managed just 2%.

“This is one of the key drivers for us in the transportation sector; we need to get our act together,” he says. “The question is, to what extent can a diesel car survive? And we have the challenge of the gasoline ICE, which needs to demonstrate how low it can go in fuel consumption and efficiency.”

“This is one of the key drivers for us in the transportation sector; we need to get our act together,” he says. “The question is, to what extent can a diesel car survive? And we have the challenge of the gasoline ICE, which needs to demonstrate how low it can go in fuel consumption and efficiency.”

Green electricity

There is no doubt that the speed of change in mobility is currently in an accelerated development phase. Electric vehicles are becoming commercially available at affordable prices and charging points are beginning to feel routine.

Electric vehicles are great provided the electricity is itself ‘green’. This comes back to the question of power generation and our continuing reliance on fossil fuel for energy. Whether it’s burnt at a power station down the road or in your engine, the process of combustion – by its very nature – creates emissions.

Today, emissions from electricity and heat production represent around half of the CO2 produced globally. Despite power station gas turbines having around twice the thermal efficiency of internal combustion engines, on the scales needed for a full transition to electric vehicles, it would likely result in more fossil fuels being burnt to supply the necessary increased baseload to the grid. So, are we in danger of shifting the problem from tailpipe to chimney stack?

“A move to renewable energy is almost mandatory if we want to get to zero-emissions,” says Dr Warnecke. “The difficult issue is that production of electricity must address the cyclic and irregular consumption of electricity, and renewable production of electricity, which is also intermittent. In this case, an electric vehicle could be an enabler for renewable energy knowing that we have intermittent production and cyclic demand. An electric vehicle could be used for micro-mass-storage knowing that most vehicles are parked 90% of the time.

“We have a few decades in which we’ll see a heavy transition in energy. For [Shell], that’s a challenge, but we truly believe that by the end of the century we will have completely moved to renewable energy sources. The name of the game is how to make use of non-fossil energy and phase out fossil fuels while also having the power available at the right time, at the right place and at affordable prices, and electric vehicles can help us achieve this.”

Electric revolution

The introduction of Tesla as well as electric vehicles from more established brands like Nissan with its Leaf and the Renault ZOE have made electric vehicles broadly accessible and affordable to the masses. However, even with the most persuasive marketing, electric vehicles must offer consumers some advantage. The reality, however, is that consumers will likely need to compromise, quite heavily, as the technology develops.

Production volumes, too, are some way off reaching the scales recognised as ‘mass market’, currently making up around 0.2% of total ‘light-duty’ cars sold in 2016. However, if the consumer is sceptical, the automotive industry is fully embracing electrification as the future.

“We are at the beginning of real and big growth for EVs,” says Rémi Bastien, vice president for automotive prospects at the Renault Group. “Many people consider the emergence of EVs to be very slow. But, if we compare the beginning of EV to hybrids, we can see even if the number of EVs is quite small, the ramp up has been much faster than for hybrids. Taking a forecast in Europe and China, we can see growth is 60% per year, which could lead to 2% of the market worldwide for EVs by 2020.”

And it’s not just the automotive industry. With EU regulators trapped in negotiations elsewhere, it is quite plausible that future targets will come from cities, which could simply ban internal combustion within certain city limits. Both London and Paris have recently stated they want petrol and diesel cars banned by 2040, with diesel being singled out to be banned as early as 2025 with possible emission levies being charged to diesel drivers before that.

“If you want to engineer for one trend, engineer for this one,” says Michael Hurwitz, director of transport innovation at Transport for London. “We need to find a way of getting around that doesn’t pollute the air and that’s sustainable.”

In London, all new single-decker buses will be zero-emission by 2020, there will be zero-emission capable taxis from 2018, and all taxis including private hire vehicles will be zero-emission capable by 2021.

“One thing you can guarantee is that it will be ratcheted up in terms of stringency on air quality,” continues Hurwitz. “We are talking about having a zero-emission zone in London by 2025.

“We have a Mayor in London that is a sufferer of adult onset asthma and air quality is a top priority. We have to accept that the VW emissions scandal has changed the opinion of policy makers and the public.”

“We have a Mayor in London that is a sufferer of adult onset asthma and air quality is a top priority. We have to accept that the VW emissions scandal has changed the opinion of policy makers and the public.”

Hybrid ramp-up

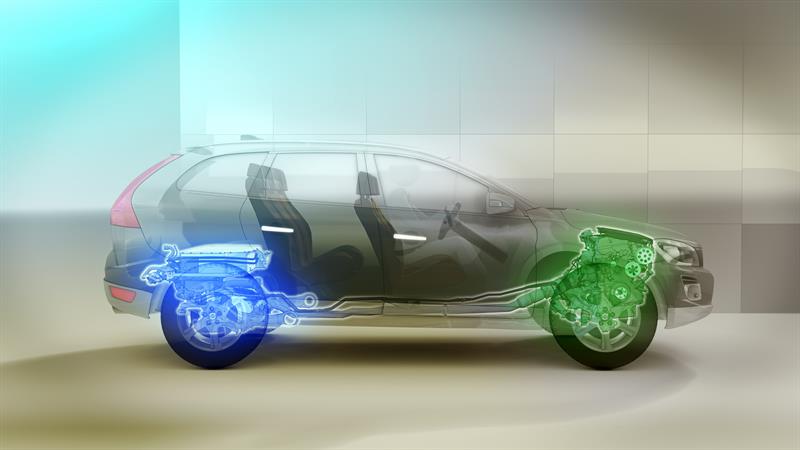

Manufacturers are coming to the conclusion that lightweighting, for the time being, is only going to go so far. It means the ramp up of hybrid vehicles is expected to gather pace in the next few years as the industry’s ‘secret sauce’ to help make up any shortfall of the 95g of CO2/km emissions cap effective from 2021.

In July, Volvo was probably the first of many major OEMs to announce that it will stop the production of internal combustion-only cars from 2019, and pursue a strategy in the short-term toward hybrids as it develops enabling technologies for electric vehicles and the corresponding infrastructure is put in place.

“What we want to achieve is no CO2 emissions but we also need to be pragmatic and consider what is affordable to the customer,” says Bastien. “The electric vehicle is a necessity for the automotive industry as the end game is all-electric. The question is how long will it take… but we are on the cusp of a transformation.”

With Paris and now London aiming for combustion free city centres by 2040, this could become the next significant target for the automotive industry after 2020. And it would mean that by 2040 we’d have said our goodbyes and extinguished the internal combustion engine.

“We are not going to put a deadline on when we will phase out petrol or diesel cars, but it is obvious that the whole industry is moving away from fossil fuels,” concludes Bastien. “It means the long-term future for powertrain will be electric vehicles with batteries and then probably with fuel cells [beyond that]. So, for carmakers we have a big challenge.”

The Electric business model

Renault’s ZOE is sold without a battery, which makes the purchase cost similar to a like-for-like internal combustion engine car. As the cost of charging an electric car is much lower, Renault say that when combined with battery rental, the cost for an electric vehicle is relatively similar. “It’s important we find a way to help customers not be surprised by their introduction to electric vehicles,” says Rémi Bastien, vice president for automotive prospective at the Renault Group. “We must drive three disruptions at the same time. The first is to get rid of subsidies from government so the total cost of ownership gap with ICE is cancelled out. “If we want an EV to be the first car in the household we also need to overcome the limitations of range. And we must ensure the best connection with the micro grid, which brings value to the EV.” |