It’s in stark contrast to the space industry, generally, which has struggled to remain relevant in the fast-moving data-lead connected world of recent years. That’s not to say the space industry is contracting, far from it. The UK’s space industry alone continues to grow over 8% per year, with annual turnover in excess of £11 billion.

However, public interest in space has long been waning despite society’s current technophilia. Many no longer see it as cutting edge, but rather an old fashioned, aging and mature industry struggling to modernise.

Astro-physicist Duncan Law-Green has been a lifelong space enthusiast and runs the UK blogging site, Rocketeers.co.uk – summing up his own feelings, he says: "Communications satellites are worthy, but dull. It’s rocket engines, space tourism and space planes that have always been the real interest."

While the very thought of spaceflight was once enough to capture the imagination, European space activities appear faceless, sterile and clinical. Unless there is a catastrophic explosion, launches rarely make mainstream news.

Things are changing though, and quickly, both here and abroad. There is no doubt the ‘Tim Peake effect’ has gone a long way in winning back mainstream hearts and minds that space is still relevant.

"It’s certainly helped public visibility," says Law-Green. "And it’s helped in the political arena. If you compare Government attitude now with 20 years ago, it’s night and day."

Today, Government support for the space sector is active and strong. It is closely following developments in the US to learn lessons and has an open dialogue with space industry stakeholders to encourage commercial space development.

"I look at the [Government’s space] policy now and it’s hard to find anything to change about it," adds Law-Green. "When does anyone ever have that attitude about any Government policy? It is astonishing, but we ought to give them credit."

The headlines created by Tim Peake have shown the world that the UK can, and does, play an active part in the space industry. It is, however, another breed of adventurer that looks set to modernise what many see as an expensive slow moving industry.

Claire Barcham is the satellite launch programme director at the UK Space Agency (UKSA). She says: "Entrepreneurs are now leading the way in innovative advances in the space sector, globally. We see a number of new entrants in the market, all jostling with well-established larger companies in the space sector. It’s creating exciting opportunities for those brave enough to grasp them."

Fearless ambition

Fearless ambition

Elon Musk, the man behind SpaceX, is the personification of this new breed of entrepreneur. Alongside Tesla, and the ongoing development of hyperloop technologies, Musk has made it his mission to develop low-cost, reusable, and efficient access to space. His rapid development of reusable launchers has set out a clear aim: improve reliability and ultimately reduce launch costs by a factor of 10.

Though clearly the poster child, Musk is not the only one to see the opportunities being created by fledgling commercial space. "There is an awful lot more going on in commercial space than just SpaceX," says Law-Green. "Virgin Galactic, for example, is not just working on SpaceShipTwo, but also LauncherOne. That is pretty-well advanced, and testing is being done on the rocket engine. It’s probably 12 months from first flight."

Virgin Galactic is a forerunner in the space tourism market and offers sub-orbital spaceflight. The spacecraft design is noted for its configuration of two separate vehicles – a surrogate aircraft to take the spacecraft up to around 50,000ft before the spacecraft is dropped and the rocket ignited.

However, it is the development of its LauncherOne that holds significant promise for commercial space  opportunities. The plan is to use a Boeing 747 as the surrogate aircraft to fly the launcher to 40,000ft where it is dropped and the rocket fired. Virgin Galactic’s aim is to offer viable lower-cost deployment of small satellites and could rival SpaceX, especially for smaller satellites deployed in a Sun-synchronous orbit. It’s clear Virgin Galactic, and Sir Richard Branson, are here for the business likely to be created. Musk’s ambitions, by contrast, goes well beyond technical, business or market opportunities. His goal, and mission statement, is to allow people to live on other planets. Despite forming in 2002, SpaceX is already able to launch, land and reuse liquid fuelled rockets on floating drone platforms out at sea, with his Falcon 9 series of launchers that are also running resupplying cargo missions to the International Space Station (ISS).

opportunities. The plan is to use a Boeing 747 as the surrogate aircraft to fly the launcher to 40,000ft where it is dropped and the rocket fired. Virgin Galactic’s aim is to offer viable lower-cost deployment of small satellites and could rival SpaceX, especially for smaller satellites deployed in a Sun-synchronous orbit. It’s clear Virgin Galactic, and Sir Richard Branson, are here for the business likely to be created. Musk’s ambitions, by contrast, goes well beyond technical, business or market opportunities. His goal, and mission statement, is to allow people to live on other planets. Despite forming in 2002, SpaceX is already able to launch, land and reuse liquid fuelled rockets on floating drone platforms out at sea, with his Falcon 9 series of launchers that are also running resupplying cargo missions to the International Space Station (ISS).

Nasa, by comparison, has struggled to keep up with this engineering tenancy. Despite setbacks, delays and even catastrophic failures, SpaceX continues to develop at speeds that would simply not be thought plausible by the traditional space industry.

It was SpaceX’s announcement earlier in February, however, that really shook the global space industry’s very foundations. In it were details that two space tourists will be flown to the moon and back in 2018.

Nasa has been developing a replacement for the Space Shuttle for more than a decade and will be ready for its own first test flight at around the same time as SpaceX’s moon endeavour. So, is this the end for Nasa as a launch developer? Musk himself is outspoken about potential competition and comparison with Nasa, tweeting last month, ‘SpaceX could not do this without NASA’ after the moon ambitions were announced. In fact, many suspect a closer relationship between Nasa and SpaceX as Musk moves towards his goal to send humans to Mars as soon as 2022.

Nasa has been developing a replacement for the Space Shuttle for more than a decade and will be ready for its own first test flight at around the same time as SpaceX’s moon endeavour. So, is this the end for Nasa as a launch developer? Musk himself is outspoken about potential competition and comparison with Nasa, tweeting last month, ‘SpaceX could not do this without NASA’ after the moon ambitions were announced. In fact, many suspect a closer relationship between Nasa and SpaceX as Musk moves towards his goal to send humans to Mars as soon as 2022.

The operational success of SpaceX is a statement that commercial space is viable and it is here. Forget slow development, big budgets, uncertain leadership, an uncertain technology roadmap – that is for old space. New space is faster, leaner, smarter and has billionaires backing the charge.

UK perspective

The question is, can the UK capitalise on the opportunities afforded by new space? As a sector, space is one of the UK’s success stories, having bolstered its position since the early 2000s. The UK space sector is worth well over £14 billion, has a 7% share of the global space revenues and employs nearly 40,000 people.

Space has been targeted by the Government as an industrial success story for growth, and the opportunities afforded by commercial space have promoted investment. The UK Space Agency has already awarded just under £150,000 to three business incubation centres across the UK, to support entrepreneurs and small companies in the space industry, which comes in addition to a £10 million scheme to incentivise the UK’s commercial spaceflight.

The rhetoric is strong, with Lord Ahmad, Minister for Aviation, saying: "It’s our ambition as a Government, as a collective industry, as a country, that the UK is the best place in Europe for space flight operations."

Last month legislation, known as the Spaceflight Bill, was published to facilitate and regulate commercial spaceflight in the UK. It’s clear that the Government wants to be commercial space enabled as soon as possible and send a strong message that the UK is on board, and will be ready for launch, as and when, commercial launchers become available.

That message was echoed by Universities and Science Minister Jo Johnson, who says: "The traditional space sector is changing and the way we access space is changing too. It’s vital that we don’t miss the exciting opportunities that are now ahead of us."

Estimates put the commercial spaceflight market at around £25 billion over the next 20 years. Today, though, grants worth £10 million are being made available around the UK to help develop the commercial launch capabilities needed for satellite deployment and space tourism.

"The development of launcher capabilities really needs to go hand-in-hand with the development of a spaceport," says Barcham. "We want to ensure that from 2020 we have both a spaceport that is operational in the UK, and also a launch service provider that is really committed to operating from that location – to offer spaceflight for science and paying passengers."

Success requires a symbiotic relationship and any potential spaceport should reflect the design of the vehicles it is looking to serve. For example, will the launcher be a SpaceX style vertical take-off and landing configuration, or more like the classic runway configuration that is being used by Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic?

"What we are hoping to see from our call for funding proposals is the full range of options available," says Barcham. "We are open to proposals from anyone – from companies with a large global footprint and a long-established heritage in the space sector to new entrants in the market with an exciting idea."

The idea of a spaceport being built and operational in the UK within three years might well seem preposterous to many, especially given the delays that other transport infrastructure projects typically endure, such as Heathrow’s third runway and HS2/3. However, any UK launch site is likely to be ‘no-frills’ and a vertical launch site with barebones infrastructure on a Scottish isle, for example, suddenly seems far more viable in the cost and timeframe suggested. Rather than needing a full length runway, a vertical launch site footprint might only be slightly bigger than a helipad.

"It is undoubtedly ambitions, but this is achievable," says Barcham. "We are not the only country looking at this as an exciting opportunity to develop. Other countries are pursuing this market, so it is important we act with suitable speed and determination… What we want to do is create the right conditions in the UK so that industry is prepared."

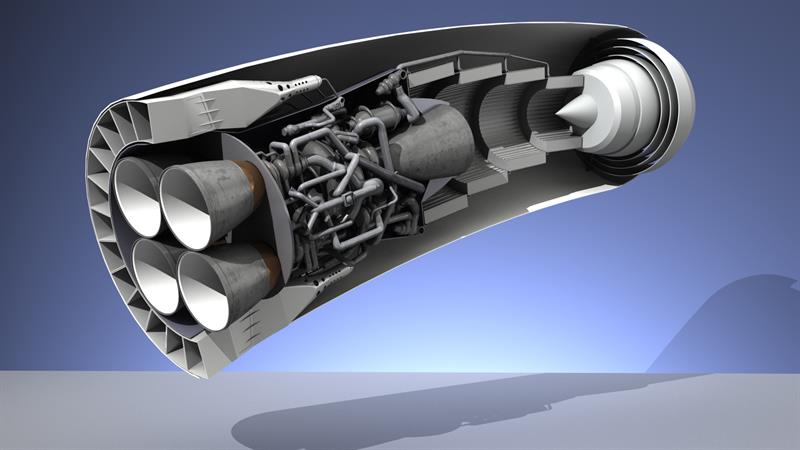

It's all irrelevant anyway No space article would be complete without mentioning Alan Bond and the ongoing work at Reaction Engines to develop the SABRE (Synergistic Air-Breathing Rocket Engine). The holy grail for space access has always been single-stage to orbit (SSTO), and Reaction Engine’s air-breathing rockets seems the most likely technology to succeed at present. Should he be successful, it is likely to lead to a step-change in space access cost and capability, similar to Whittle’s turbojet engine and the effect that has had on commercial aircraft. "Propulsion work has been bubbling along for a while and is now picking up a bit with Reaction Engines getting funding and the stimulus for the spaceport works," says Astro-physicist Duncan Law-Green, a lifelong space enthusiast who runs the blogging site, Rocketeers.co.uk. So, will it be Alan Bond that will break the back of Single Stage to Orbit? "There are any number of paper designs about how to do it," says Law-Green. "But from the point of view of building hardware, Alan Bond and Reaction Engines is certainly out in front. But it is such a large, expensive and long term project, it is hard to say. You compare it with how rapidly SpaceX is coming out with new models of launch vehicles, every few months almost, and the SABRE is at least a 20-year project. SSTO will happen but it will take some time and some considerable investment. Whether Alan Bond gets to it as the tortoise or some other entity like a US commercial body catches him in the late 2020s is anyone’s guess. But I suspect he will succeed." |

Build it and they will come: Lessons from America

Astro-physicist Duncan Law-Green has been a lifelong space enthusiast and runs the blogging site, Rocketeers.co.uk. He says: "The UK Space Agency is learning from the experiences of what has gone before it in the US and is determined not to make the same mistakes. Space Port America is based on state funding and cost several hundred million dollars. It has a fancy terminal building and runway in the middle of the dessert, which is all very impressive… but it has sat there empty for the past couple of years as there hasn’t been anything ready to fly from it." The UK Space Agency has been determined not to do the same thing by not committing to elaborate hundred-million pound plus facilities. It is making sure the UK can operate a lean, barebones but capable facility, that has been developed with a launch vehicle partner, and optimised for a particular launcher – be it vertical take-off and landing, more traditional runway take-off and landing, or a combination of the two. |

The US has been the prime mover for commercial space for some time. Being first to market has its advantages, but it also means that the competition can learn from your mistakes. As the Government announced plans to commission an operational UK spaceport by 2020, it did so with the benefit of Spaceport America based in New Mexico.

The US has been the prime mover for commercial space for some time. Being first to market has its advantages, but it also means that the competition can learn from your mistakes. As the Government announced plans to commission an operational UK spaceport by 2020, it did so with the benefit of Spaceport America based in New Mexico.