Its applications are being adopted in other sectors such as medical and automotive as a potentially faster and more economical alternative to traditional manufacturing methods for certain applications. Though it offers huge potential to the oil and gas arena, its uptake so far has been limited. The industry’s risk-averse culture, lack of infrastructure and stringent standards have been cited by leaders as barriers to adoption.

Yet, as experienced in other industries, the technical and economic benefits far outweigh the obstacles. The oil and gas industry’s growing focus on operational efficiency in today’s low price climate is slowly driving change and a realisation that the challenges are not insurmountable.

Two main groups of technologies can be of benefit to the oil and gas industry: powder bed fusion and direct energy deposition. Both use a diverse range of metals in wire and powder form, which can be fused together using lasers, electron beams and electric arcs.

Asset life extension

For ageing oil and gas assets, replacement components may be difficult to source, require a long lead-time to manufacture and incur significant expense to produce.

Stephen Fitzpatrick, senior manufacturing engineer with the University of Strathclyde’s Advanced Forming Research Centre (AFRC) believes the direct energy deposition additive technique called laser metal deposition could be the answer to re-manufacture difficult to weld oil and gas components, such as those made of corrosion resistant steels and heat resistant super alloys.

He says: “Currently, no re-manufacturing procedures exist for some high value components, but by applying additive material to a specific area that’s worn; you can extend the life of a component, and increase its functional performance. This could play a key role in enabling oil and gas operators to reinstate their existing old equipment, reduce lead-time, allow options to extend maintenance schedule cycles, and increase functional performance.”

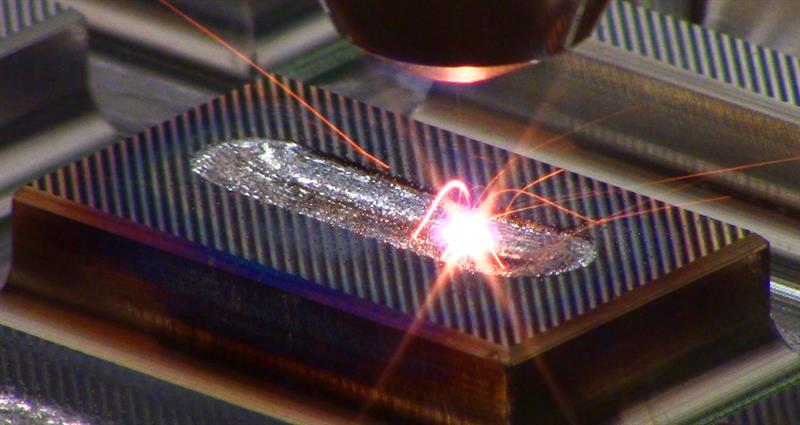

Laser metal deposition is a powder additive manufacturing process where powders are conveyed through a nozzle and a laser is used to melt the layer of powder into a desired shape. According to Fitzpatrick, this process offers many benefits for the oil and gas sector and in particular, for re-manufacturing applications.

“It has very fast cooling rates, which creates a very fine microstructure,” he says. “There is also very low dilution and heat-affected zone into the substrate material, meaning that thinnerclad layers can be applied whilst still ensuring that the clad composition is achieved.

“A secondary benefit to lower dilution and a small heat-affected zone is that there will be shallower residual stress profiles, meaning very little distortion of components. This process can be applied very accurately meaning fine features can be achieved with minimal post-process machining. Alloy powders can also be mixed together to create new alloys that can be functionally graded to obtain tailored properties.”

Though this technology has been around for several years, its adoption has been slow, which may be due to a lack of control and insight into the process.

“With growing research, advanced optics and the availability of high powered lasers achieving the correct parameter windows, the additive process is realising its potential,” Fitzpatrick explains: “This is particularly relevant for remanufacturing applications where old assets can be reinstated into service to last beyond original design life. In some instances, there is an opportunity to avoid unnecessary scrapping and increase performance to that greater than the original component. Overall, this will have a significant economic impact for oil and gas businesses.”

The AFRC is currently investigating deploying laser metal deposition for remanufacturing of aging assets, such as shafts, valves and pumps and as an alternative to traditional cladding of valves. A development process is initially undertaken so that porosity is mitigated and the correct parameter windows are identified to provide a quality output. This can then be tested and validated.

Building complete parts

There are other direct energy deposition technologies that could also have a big impact on the industry.

“A lot of oil and gas companies are also looking at wire arc additive manufacturing to start building complete parts,” says Fitzpatrick. “This method allows you to build a component from nothing to a near net shape state. Again, this isn’t a new process. It makes use of traditional gas metal arc welding techniques to build large structures, and offers the potential of improved material utilisation, extremely short lead times and overall cost reduction.”

The potential of offshore 3D printing

Additive layer manufacturing, a form of 3D printing, also offers significant opportunities. The use of powder bed fusion additive processes to manufacture spares for instance, is likely to increase, helping to save costs from not having to carry inventory. Other benefits include being able to rapidly produce complex prototype geometries and the consolidation of various parts into a single manufactured component bespoke to requirements, that may be difficult, if not impossible, to make using standard manufacturing techniques.

As manufacturing needs not be constrained to a complex fabrication facility, further reaching benefits for the oil and gas industry also include reduced supply chain as well as the future potential to produce parts quickly, when required, on an offshore asset, which could reduce the risk and costs of downtime.

Additive manufacturing and composite material systems will undoubtedly continue to replace many of the traditional uses of formed metallic parts and materials in the oil and gas industry. However, there are still an important set of conditions when forged and formed components are unquestionably the right answer – both economically and technically – to a particular design or manufacture challenge.

Research carried out by the AFRC has shown that additive manufacturing can offer opportunities to improve existing routes of material production or even to replace some of them. However, further research is needed to fully understand the influence of different process parameters on microstructure and properties of the final product.