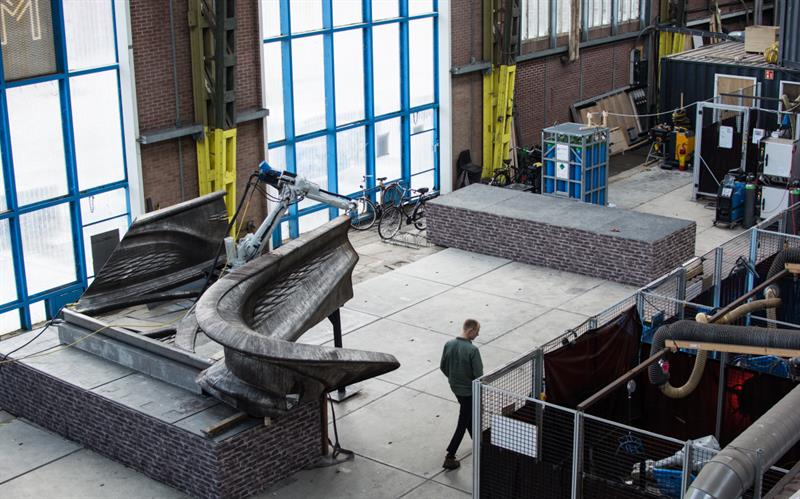

Amsterdam-based start-up MX3D is 3D printing a 12-metre-long stainless-steel pedestrian bridge to be installed across the busy Oudezijds Achterburgwal canal in the old city centre later this year. The concept is relatively simple: put a welder on a robot arm, place one on either side of a waterway and begin ‘printing’ until they meet in the middle. Easy, right?

Chief technology officer from MX3D, Tim Geurtjens, explains: “When we started we thought let’s get an old robot arm – the kind you see on car production lines – and put a simple €1000 welder on the end. We thought, ‘this is going to be easy’. But things turned out to be much more complicated.”

Broadly speaking, the technology is about adding layers of material. However, MX3D is not using modern additive techniques like selective laser melting (SLM) or even direct metal laser sintering (DMLS). Instead they’ve chosen a more traditional process… welding.

Broadly speaking, the technology is about adding layers of material. However, MX3D is not using modern additive techniques like selective laser melting (SLM) or even direct metal laser sintering (DMLS). Instead they’ve chosen a more traditional process… welding.

“It is a MIG welding technique,” says Geurtjens. “It is melting the base material and adding a metal wire and that is fusing together. We are basically building with molten metal.

“One of the most complicated things was to get control of the welding process. You can study welding for your entire life and still not know everything about it. It is a very synergic process – if you change one value, everything changes as well – we really underestimated that.”

While the team initially considered printing the bridge in steel, they quickly moved towards stainless steel to overcome problems of corrosion. Using steel would have meant that a coating would be needed, which would completely cover the bridge’s surface, hiding the fact it was made of steel and more importantly the fact it had been 3D printed.

“Changing material to stainless steel was a very expensive decision,” says Geurtjens. “Stainless-steel is not cheap but this is maybe the only 3D printed bridge we are ever going to make, so let’s do it right.”

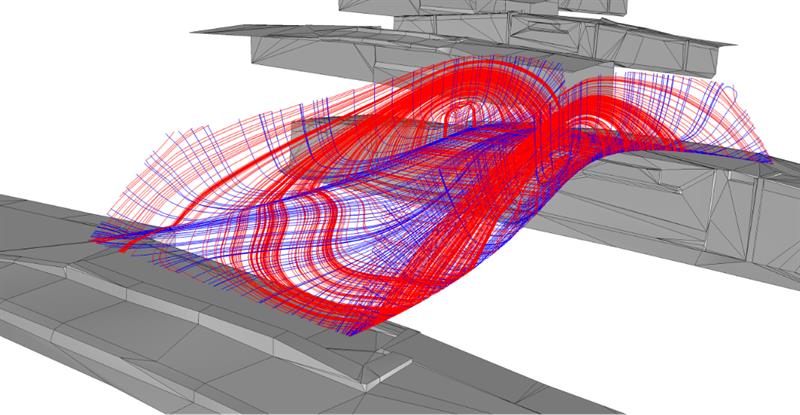

A key part was the control of the process, which was primarily driven by bespoke software that the team developed themselves to optimise all the various parameters. There was a lot of trial and error involved and while some simulation was used, the practicality of the process meant that a significant amount of practice was needed to prove out the process and properties of the printed material.

“We are developing software, parameters and printing strategies for the different kinds of 3D printable ‘lines’,” explains Geurtjens. “For instance, vertical, horizontal or spiralling lines require different settings, such as pulse time, pause time, layer height or tool orientation. All of that is incorporated in the software.”

The control is now so good that the team can print intricate structures, far more like the organic structures often printed in smaller ‘in-box’ additive machines. The process also does away with support structures due to the inherent strength of the material. This creates an ‘out of box’ 3D printing method that makes it possible to create 3D objects in almost any size.

Progress

While the concept of 3D printing a bridge in situ is an exciting and intriguing one, the practicality comes with a host of challenges, least of which is actually getting the technology to work. In short, it’s a health and safety, and operational nightmare.

As with most welding processes, sparks are emitted from the welding head which are bright enough to damage eyesight if looked at directly. In addition, getting the necessary permits to build the bridge would be a long winded, if not impossible, undertaking. The other difficulty is that access to the site would be limited due to the narrow streets.

“From the beginning, we knew we wanted to have the bridge there,” says Geurtjens. “But we walked around and thought this is never going to work. We’d need to set up shop there, so have an office, power supplies, shield everything off, shield off the robot and welder from the weather and weatherproof the equipment. The logistics and cost would make it very difficult.”

The team therefore decided to create a lab in which to develop the process and begin fabrication of the bridge as intended. Once built the bridge could be tested and put through the necessary rigour required for a public foot bridge, before it could be transported, assembled in place and commissioned. To date, the team has fabricated half the bridge using the technique and expect to complete fabrication within the next few months.

Smart bridge

Given the pioneering nature of the build, the process has numerous permutations as well as the possibility of voids produced during printing or perhaps the inclusion of oxides on the material. It means it’s difficult to know how the structure will hold up over time. To answer this question, the team plans to lace the structure with sensors to measure, monitor and analyse the performance of the bridge which, upon completion, will be the world’s largest 3D printed metal structure.

The sensors will collect data on structural measurements such as strain, displacement and vibration and measure environmental factors such as air quality and temperature, enabling engineers to measure the bridge’s ‘health’ in real-time and monitor how it changes over its life.

Geurtjens explains: “We will make the bridge a smart bridge by fitting it with all kinds of sensors and accelerometers as well as measuring temperature and humidity – basically any sensor we can lay our hands on we’ll put on the bridge and start measuring. First of all though, we will measure the structure’s integrity.

“Obviously, to get a permit for the bridge is quite challenging as it is very hard to prove that a new material and process like this is actually strong enough to be used. So, we will do some full load tests, equivalent to 300 people on top of it to measure deformation and measure the health of the bridge.

“But we won’t stop there. What we will do is measure structural integrity and see what the bridge does. Then afterwards, we’ll leave the sensors there, so when we put the bridge on location we will keep measuring and generating data from it.”

Autodesk is supplying the cloud services that will power the bridge’s data collection and processing. MX3D is also working with researchers from The Alan Turing Institute to develop machine learning algorithms that will enable the bridge to interpret its environment. This data will also allow MX3D to ‘teach’ the bridge to understand what is happening on it, such as how many people are crossing it and how quickly.

The data from the sensors will also be input into a ‘digital twin’ of the bridge, a living computer model that will reflect the physical bridge through its life, with growing accuracy in real-time as the data comes in. The performance and behaviour of the physical bridge can be tested against its digital twin, which will provide valuable insights into designs for future 3D printed metallic structures. It will also enable the current 3D bridge to be modified to suit any required changes in use, ensuring it is safe and secure for pedestrians under all conditions.

“We have a complete digital model of the bridge and have done some strength analysis on it,” says Geurtjens. “We then have to validate the digital model of the bridge by doing some physical tests as we need to make sure the theoretical situation is the same as the real situation.”

As well as the material and process, there is also the potential for unknown behaviour in the hollow structure. Does a 3D printed hollow beam, for example, have the same buckling and failure modes as a normal hollow extruded steel beam?

“That is an issue,” says Geurtjens. “There is a little bit of lattice work inside, and we thought about printing a full lattice inside but it didn’t prove to be necessary. The design was made in collaboration with the engineers from Arup and the idea was, first of all, let’s look at what kind of loads can be placed on a bridge and how that would affect the design.”

Future potential

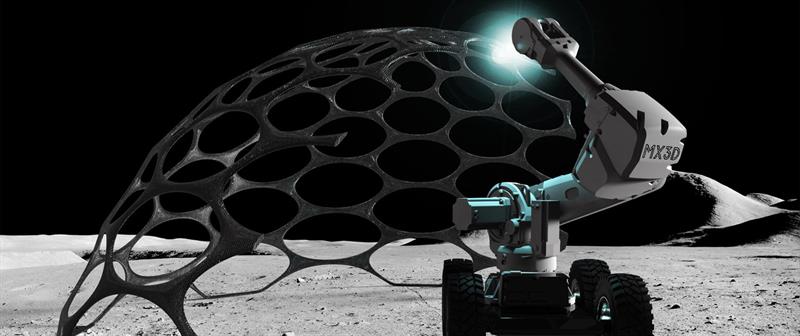

The future for the techniques being developed by MX3D are as wide and varied as you’d expect from such a project. From a building and fabrication point of view it is envisioned that the robot and welding arm could be turned into moving fabrication robots. The vision is that the robotic arms will be placed on wheels that can drive around a site, for example, in  swarms and produce anything from bridges to bike frames. The technology could even be sent to the moon where it could produce structures for colonisation.

swarms and produce anything from bridges to bike frames. The technology could even be sent to the moon where it could produce structures for colonisation.

“We spent a year and half testing and developing the techniques and have come up with a strategy that’s worked really well,” says Geurtjens. “It was just a bit too slow for now to do on the canal, but the most important thing is we get the bridge done. The dream is still there for the next project to print in this way. But, with the first project we figured it is more important to get it there.”

Data to design The engineers at MX3D use Lenovo’s ThinkStation P910 for its extreme performance edge to handle all of its data and run topology optimisation applications like Autodesk Fusion 360.

|